Livecoding Side By Side Content in VR

Wed 06 July 2016

Michael Labbe

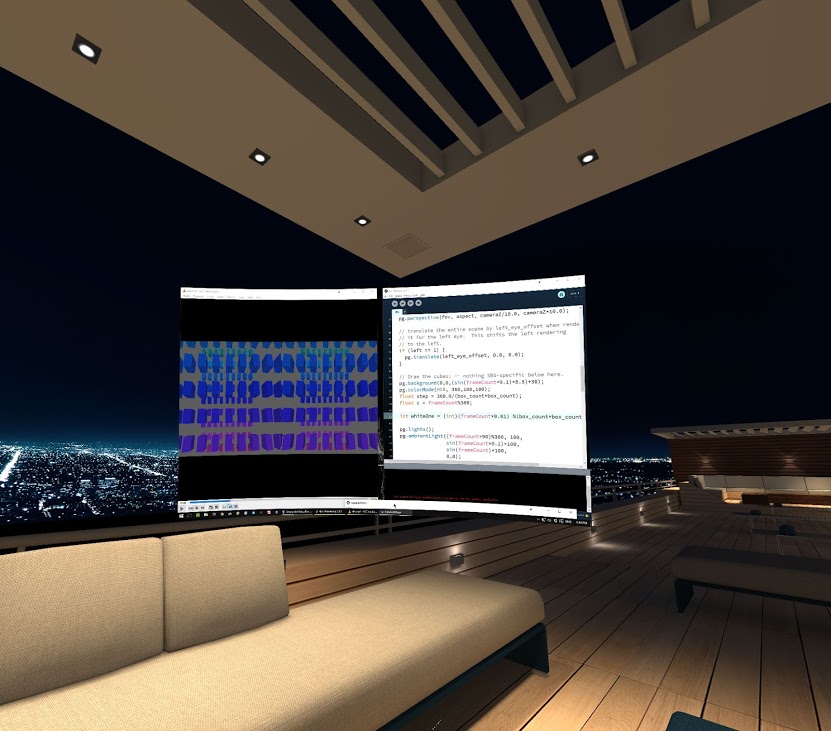

One of the really cool things about social VR is that a little technical know-how can go along way. Recently, I have been exploring social VR through BigScreen VR, an app that lets you see your monitor in the context of a large virtual room, shared by others. Imagine a virtual LAN party and you have a good idea about what’s going on.

Quietly, they dropped an SBS mode into the “Beta Features” menu. All of a sudden, it is possible to socially livecode 3D content in a VR world. And, it’s possible to do this with a top-to-bottom free software stack. How cool is that?

What is Side-By-Side (SBS) content? Check out this Youtube video to immediately get a sense of what is going on. In SBS videos, the image for each eye is encoded using half of the video framebuffer, with a small horizontal offset in the camera position. If you watch this in a side by side video app, each eye only sees the half of the video. Your brain is tricked into thinking it is seeing 3D objects. Leaning side to side even triggers a sense of parallax.

Because BigScreen shares your screen, you can develop software and test it right inside your VR headset. Enter Processing, a free visual coding environment with support for 3D rendering and offscreen framebuffers.

In order to render SBS content in Processing, you simply have to render to two offscreen framebuffers, offsetting them from each other.

Here is sample code with comments that demonstrates exactly how this works. You can copy and paste this into a Processing 3 IDE window and just run it.

If you are simply curious, this YouTube render shows what the Processing sketch looks like.

Git-Svn Considered Harmful

Sun 31 May 2015

Michael Labbe

#code

Git-svn is the bridge between Git and SVN. It is more dangerous than descending a ladder that into a pitch black bottomless pit. With the ladder, you would use the tactile response of your foot hitting thin air as a prompt to stop descending. With Git-Svn, you just sort of slip into the pit, and short of being Batman, you’re not getting back up and out.

There are plenty of pages on the Internet talking about how to use Git-svn, but not a lot of them explain when you should avoid it. Here are the major gotchas:

Be extremely careful when further cloning your git-svn repo

If you clone your Git-svn repo, say to another machine, know that it will be hopelessly out of sync once you run git svn dcommit. Running dcommit reorders all of the changes in the git repo, rewriting hashes in the process.

When pushing or pulling changes from the clone, Git will not be able to match hashes. This warning saves you from a late-stage manual re-commit of all your changes from the cloned machine.

Git rebase is destructive, and you’re going to use it.

Rebasing is systematic cherry picking. All of your pending changes are reapplied to the head of the git repo. In real world scenarios, this creates conflicts which must be resolved by manually merging.

Any time there is a manual merge, the integrity of the codebase is subject to the accuracy of your merge. People make mistakes — conflict resolution can bring bugs and make teams need to re-test the integrity of the build.

svn dcommit fails if changes conflict

This might seem obvious, but think of this in context with the previous admonishment. If developers are committing to SVN as you perform time consuming rebases, you are racing to finish a rebase so you can commit before you are out of date.

Getting in a rebase, dcommit, fail, rebase loop is a risk. Don’t hold on to too many changes, as continuously rebasing calls on you to manually re-merge.

When Git-SVN Works

Here are a handful of scenarios where git-svn comes in handy and sidesteps these problems:

- When you are running a quick experiment and don’t intend to

dcommitback to SVN. - When you aren’t extensively cloning, or branching the code once it’s in Git.

- When you can guarantee that SVN will sit idle while you work in Git.

100m People in VR is not the Goal

Wed 07 January 2015

Michael Labbe

#biz

One hundred million people in VR at the same time isn’t a goal — it is the starting point.

The real goal is obtaining the inherent user lock-in related to hosting the most accurate simulation of materials, humans, goods and environments available. As we approach perfecting simulation of aspects of the real world, things that we used to do in the real world will now make sense to do in a VR context instead.

This upward trend will intersect another: real raw materials are increasingly strained, forcing the cost of production for goods beyond the access of the middle class. For activities that can be well simulated in VR but require hard to access materials to do in the real world, VR becomes a reasonable substitute.

Early VR 2.0 pioneers have talked about the opportunity to create a game that caused a mini-revolution like Doom did. That’s small potatoes. We are talking about a platform with control of artificial scarcity with the ability to make copies of goods for fractions of a penny. The winners in this game are the controllers of this exclusive simulation.

In this environment, Ferrari’s most valuable assets are going to be its trademarks many times over anything else it holds.

Dominoes will fall. VR headsets are the leaping off point, but not the whole picture — haptic controls, motion sensors, binaural audio interfaces, the list goes on. As each improves, more activities will make sense to perform in a virtual environment.

Looking back twenty years, referring to VR as a headset is going to seem trite. The world is changing from a place that “has Internet” to a place that is the Internet, and for the first time, you only have to extrapolate the fidelity of current simulation technologies to see it.